Health warning: this post contains detailed information about cataloguing and classifying and is not for the faint-hearted!

I’m six weeks into my job on the Antarctic Cataloguing Project at The Polar Museum and am finally starting to feel that I’m getting to grips with the project and all its different elements. I’ve been doing quite a bit of behind-the-scenes work and trialling of this and that – including devising a standard template for biographical records for people, organisations and expeditions so that this information doesn’t get repeated in individual object records; creating a term list for Arctic and Antarctic expedition names so that they always appear in the same format; and measuring and describing some of the 27 objects in the collection from the British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09 (Nimrod) and cross-referencing them with photographs from the expedition. I’ve concluded that a two-pronged approach to the project is probably the way forward – one driven by the objects and the other by the expeditions – and I hope the two will come together at some point! And I’m really hoping that, come the new year, I’ll be ready to get properly stuck in.

I’m also working on a standard template for object records, and am currently thinking about keywords – what sort of keywords have been used in the past, what keywords will be useful to us (internally), what keywords will be useful to the public (externally), and what’s the point of these keywords anyway? I’m struggling with the answers to the first three, but I think the reason we want to use keywords is that they provide quick and easy means of searching the collections and of grouping the objects together (whether it’s by expedition, place, object type, or a more nebulous type of theme etc.)

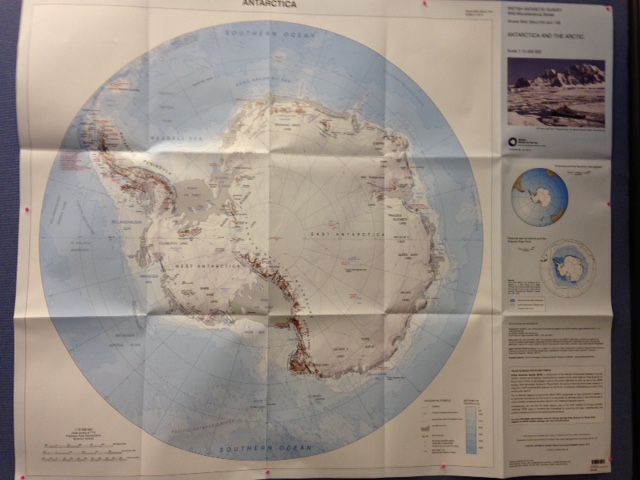

I’ve decided to focus in geographic keywords first, so I’ve been taking the time to get to know the Antarctic. I’ve been interested in the Antarctic for quite a few years but, to be honest, my geographic knowledge of the continent has never stretched much further than being able to point roughly in the direction of the South Pole and knowing where the Antarctic Peninsula is! So Step One was to get myself a map… much better!

Step Two was to try to understand how places in the Antarctic work – not only where they are, but how they are grouped together, and what the broader divisions/areas are, as well as the specific places. In short, is there some sort of hierarchy to Antarctic places – a polar equivalent of village, county, country? And I’ve discovered that the answer depends on the resources you use.

I’m a bit of a place-hierarchy obsessive, having spent the first year of my museum career on a cataloguing project which focussed on recording information about where objects were made, used and collected. Let’s imagine we have an object that was used here at The Polar Museum: we might know that it was used here, or we might know that it was used on Lensfield Road, or in Cambridge, or in Cambridgeshire, or in East Anglia or in England etc. This is why I love hierarchies – it’s great to be specific when you can, but in most cases you just don’t have enough information and need to be more generic. Another reason for favouring the generic is if an object has been used in several places in broadly the same area.

So I’ve been casting about to see whether there are any existing hierarchies of Antarctic place names and trying to understand how they work. While an existing hierarchy might not suit our needs exactly, it does mean that somebody has done the really hard part – structuring a hierarchy. In the past I’ve used the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Place Names and while (to my surprise) it does list quite a lot of Antarctic places, most places are only linked to Antarctica rather than to any hierarchy…

And then I discovered the ‘Universal Decimal Classification for use in Polar Libraries’! Exciting stuff! (Well, it is to those of us who love classifying things). It’s has been in use at the Scott Polar Research Institute since 1945 (with updates over the years) and is also used by other polar libraries, and seems to be perfect for what we want. It’s already used by the SPRI Library, is being rolled out in the Archives, and has been used in some Museum’s Arctic object records, so it makes sense to use it for the Antarctic object records too, as it provides a way to tie the Institute’s collections together and enable searching across the collections. It has taken me a little while to figure out how it works though (hence all the scribbling).

Unfortunately Step Three (the tricky one) is still to come – to work out how to put this information into the object records. A numerical code or a numerical code and text version? Should it show just the narrowest level in the hierarchy to be used for that record, or should it show all the levels, or a set number of levels? And this thinking about how to represent hierarchies in the object records doesn’t just apply to geographic keywords – they’re also issues I’m going to have think about when recording materials more subject-based keywords.

Greta

PS I promise not all of my posts will be about cataloguing and classifying!

Scott Polar Research Institute

Scott Polar Research Institute